Manual Gates, or 'GitFlow in a Wig'

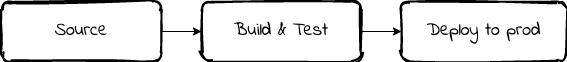

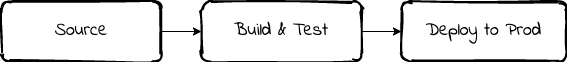

Tags: devops ci cd gitflow trunkOver last few years I’ve spent a lot of time working in the CI/CD salt mines. The simplest expression of a CI/CD pipeline is depicted below; we begin with pulling the source code, go through to a build and test stage, and deploy to an environment.

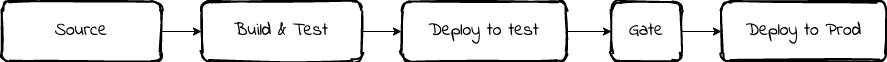

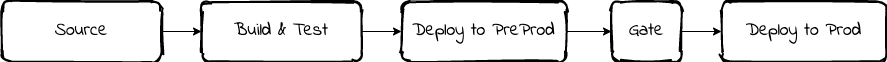

Most teams will start with this. At some point, the team itself will decide there is too much risk deploying directly to production, and will decide they need an additional environment. Enter the test (or nonproduction, or development, or QC) stage. They put in a manual gate between deployment phases and everything is fine. The pipeline starts to get used in other projects and the world keeps turning.

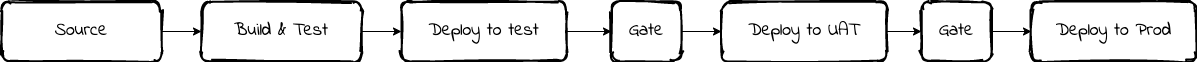

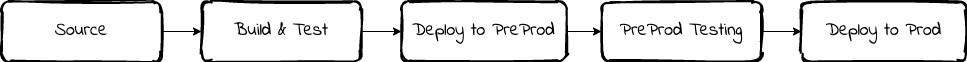

Then a new project comes along, and decides two stages isn’t enough. They want another one. It could be for User Acceptance Testing. It could be for training. At any rate it gets shoved into the pipeline between the nonproduction and production stages and the world kicks on; although the teams have noticed that this project does not deploy to production as often.

More time passes. Other teams decide they need another environment. Others add other types of verification steps into the pipeline. As they get more and more complicated, the likelihood of code getting through all the way without manual intervention decreases. Frustrated with increasing complexity, teams find ways to circument the pipeline in order to deploy manually. Incidents start to increase in frequency and duration. Engineers moving between teams are frustrated because the pipelines have wildly diverged.

Sounding familiar?

The purpose of your software is to create value for your users - the purpose of your pipeline is to ensure users can get timely access to your software. The faster you can push working functionality through your pipeline, the more value you can create for your users. Building your software delivery pipeline around this core tenent is critical to value capture. The addition of time-consuming and/or manual processes between commit (or merge) and deployment is responsible for a significant amount of drag.

First of all, nobody cares how cool your CI/CD pipeline is. - Forrest Brazeal

I’ve watched this story unfold multiple times. I’ve noticed most commonly that it arises out of a need for two things - manual gating and multiple environments. On the surface both of these things are entirely reasonable options but they seem to result in a productivity death spiral. I’ve since come to the conclusion that these are tools that one needs to have in their toolbox - the problem stems from how teams choose to implement them. I believe that these two features should be implemented via your branching model and not via discrete steps in the CI/CD pipeline. So what branching model should you use? Let’s first consider the GitFlow branching model.

GitFlow (Driessen, V. 2010) is popular branching model that was first put forward in 2010. It works by maintaining several branches that center around different scenarios; features, releases and hotfixes. It’s support for a number of different development scenarios is probably the main contributor to it’s continued popularity. A lead developer looking for a branching model is likely to come across GitFlow and several others, and select it because it addresses a number of hypothetical concerns more explicitly then other models.

This doesn’t come without cost and teams may find themselves paying for insurance they do not need. The GitFlow branching model is complicated and is reasonably strict about what branches can be merged into what target branch and the circumstances in which this happens. The number of long-lived branches increases, and I’ve seen less disciplined teams wind up in situations with conflicting versions of a product running on separate branches. This is all fun-and-games until a customer wants feature A and feature B, but these exist in conflicting versions. The only way to avoid this scenario is to dilligently ensure that everything makes it back to mainline as fast as possible. This is a key feature of another model, Trunk-Based-Development, and similar models such as GitHub Flow.

We’ve made no mystery of our dislike of GitFlow and our preference for Trunk-Based Development (Myerscough, T. 2019). We want to improve the flow of software into production thereby allowing users to get value faster. The way to do this responsibly is to automate as much testing and verification as possible and reduce the number of steps that involve human intervention. This is easiest to obtain when working in the Trunk-Based model. Merging from branch-to-branch-to-branch introduces additional steps that we feel does not add any value to the software development process, as everything should land on master eventually anyway.

But it isn’t just us. The creator of GitFlow has somewhat denounced it recently (Driessen, V. 2010), explaining that it was designed for a world in which consumers typically hosted versions of the software themselves. This is very different from the present where the typical delivery model is via SaaS-based web and mobile applications. The CEO of GitLab has raised similar concerns (Sijbrandij, S. 2015), and GitHub themselves publish their own methodology which is more in line with Trunk-Based Development (GitHub. 2020). DevOps pioneer, author of the Phoenix Project, and fellow of DevOps Research and Assessment (DORA), Jez Humble, has had similar misgivings about GitFlow (Humble, J. 2020).

never use git flow. It’s a horrible way to solve the problem the creator used it for, and also a really horrible way to build software generally - Jez Humble

Which brings me to the point made in the headline - Manual Gates are functionally GitFlow. If you are attempting to do Trunk-Based-Development, but you have manual gates between stages in your CI/CD pipeline, this is fundamentally the same as GitFlow with merging between environments. In each case someone has to manually inspect the currently deployed environment, decide whether it is healthy, then take some action to promote the software into the next environment. In each case they both have the same impacts on the flow of software into the production environment - waiting for a human to make a decision.

Are Manual Gates That Bad?

Yes. Sort of. To be honest, manual gates are only bad because 99% of the time they are used to facilitate manual testing. What about the other 1%? I believe the only time a gate is useful is to control when software hits production. You may only want deploy during off-peak times or on certain days for stability reasons e.g. if the software has all the feature it needs for an important event that will happen on Wednesday, it perhaps stands to reason to wait till Thursday before rolling out a non-essential feature.

Be aware though that the introduction of manual gates will create a disconnect between merge and deployment. This results in the “batching” of many changes that will be released to production at once. Although any pre-production testing you may have done will reduce the likelihood of an incident, the true test of anything is running it in production with real traffic. As Mike Tyson once said, “everybody has a plan until they get punched in the face”. The risk is obviously still there for smaller changes, but it can be more involved to discover what particular change was the root cause of the failed deployment. This will increase your mean-time-to-repair - a small value of which is a strong signal of a high performing software team (Forsgren, N. et al. 2018).

I’m not suggesting developers remove manual gates and leave nothing in their place. Steps need to be taken to add in automated verification to ensure promotion can proceed in safe manner and historically this has not been easy to do. It involves diverting expensive engineering effort from feature development to a support function, hence why a lot of teams tend to stick with manual review. But it is neccesary to do so, and I imagine it will become easier as more developers become accustomed to integrating it into their pipelines.

What are the tools available to you to perform automated verification of your environments in AWS? It really depends on the primitives you have chosen (containers, serverless, horse and cart etc), but here is a short list to get you started.

CloudWatch Alarms/Metrics

CloudWatch Alarms and Metrics underpin most of the automated solutions in AWS - think autoscaling groups, rollback alarms, CodeDeploy etc. Having an understanding of configuring of this is crucial to allow you to do more sophisticated automation to recover you systems. After all, you can’t respond to an event that you can’t observe.

CloudFormation Rollbacks

Most developers that have used CloudFormation will know that an error during a deployment will cause CloudFormation to rollback to a previous state; fewer seem to be aware that you can tell CloudFormation to monitor an alarm during an update, and rollback the stack if that alarm happens to enter an unhealthy state. If your deployments consist entirely of CloudFormation actions (as they may if you are building serverless applications), this may be a really easy option for you.

CodeBuild

CodeBuild has great integration with the AWS ecosystem via IAM, can run just about anything you want, and can be triggered in numerous ways (CodePipeline, API call, EventBridge etc). It will also run just about anything you want. CodeBuild can execute almost any set of instructions you may need to in order to validate your environment.

Lambda

Of course, you may not need all that CodeBuild offers so lambda might be a cheaper/simpler option for you. It integrates nicely with CodePipeline and EventBridge as well, so you could invoke a lambda function post-deploy as a means of performing automated validation.

Step Functions

15 minutes not enough to execute your tests? Maybe step-functions is more your style. Step Functions can handle long-running steps that may be nessecary for more complicated or lengthy deployments (e.g. DNS validation of certificates).

CloudWatch Synthetics

CloudWatch Synthetics is a cool, relatively new service that is capable of doing things like generating traffic for test purposes, load-testing, and taking snapshots of web user interfaces like one might do with puppeteer. Whilst it won’t handle the whole verify and rollback process, it can be useful for making the verification step more accurate and valuable.

Improving The Path To Production

It might also seem that I’m agitating for fewer environments in the CI/CD pipeline but this isn’t the case. I’m agitating for environments with a purpose behind them, of which the sole focus is ensuring the fastest and safest deployment possible. Let’s look at the below evolution of a pipeline.

- A simple pipeline is constructed that deploys straight to production

- A pre-production environment is created with a gate, in order to manually verify an environment before it reaches production.

- The tests that are run during gating are automated, there-by replacing the automated gate with automatic verification.

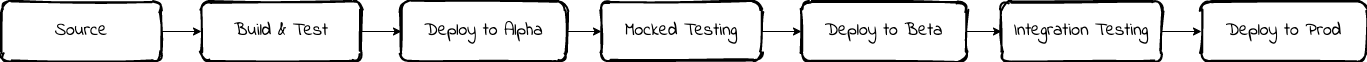

- The automated test suite begins to get slower as it both increases in size and complexity. The developers notice that this is due to bootstrapping external resources. The developers create an additional pre-production environment, and split the tests. Tests are run with mocked dependencies against the first pre-production environment, where-as real dependencies are used against the second pre-production environment.

Each of these environments is about stopping faulty or incorrect software hitting production. Concerns such as User Acceptance Testing should not block the path to production - this should have happened before code hit the master branch. Training environments should not be poached from the environments in the main pipeline. If I haven’t been clear up to this point, let me restate it - the environments that are present in your main pipeline to production should not have any other function but ensuring that you can reliably deploy code to production that will not cause an unintentional degredation.

To continue that point, I often seem teams that will have a “development” environment in their pipeline. This is a step above developers running entire copies of the system in their local environment, but it still comes with issues. It can be difficult to accurately determine exactly what is running in this environment when multiple developers are deploying changes to such an environment, which can make it difficult to ensure working code is making it’s way towards production. This is often ensures that a manual gate is introduced and that it never leaves. If developers must be able to run an isolated copy of the system, it is better to implement this via developer sandboxes or dynamic environments that are free of the pipeline. Recognise that the purpose of such an environment isn’t to safely deploy code to production, but to aide the developer in feature development, and as such it doesn’t belong in the production pipeline.

Conclusion

I do get it - writing tests that work well against live environment is hard. It feels like a better use of time in the early stages of a product to instead invest that time in the product itself and maybe it is. However if this is the situation you are in take the time to think tactically and make an informed decision. Review the list of possible ways to introduce automated testing, select what is likely to give you the best return-on-investment, and plan for when the best time to make that investment is. This could be a timeframe (we want to have this in place by the end of the year), when you reach a certain load (we need to consider this when we have 200 daily active users), or when your team reaches a certain size. Ideally teams should focus on reducing friction into production and that can only be achieved by removing steps that require human intervention.

References

[1] Driessen, V. (2010) A Successful Git Branching Model. Available at https://nvie.com/posts/a-successful-git-branching-model/

[2] Myerscough, T. (2019) Continuous Deployment - The First Step on Your Road to Recovery. Available at https://blog.mechanicalrock.io/2019/07/01/continuous-deployment-the-first-step-on-the-road-to-recovery.html

[3] Sijbrandij, S. (2015) Comment on “GitFlow Considered Harmful”. Available at https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=9744059

[4] GitHub. (2020) Understanding the GitHub flow. Available at https://guides.github.com/introduction/flow/

[5] Humble. J (2020) Available at https://twitter.com/jezhumble/status/1260930170220769283

[6] Forsgren, N., Humble, J. and Kim G. (2018) Accelerate: State of DevOps: Strategies for a New Economy. DevOps Research & Assessment.