Leaking Credentials!

# aws control tower sso organizations credentials permission policy cutoff token timestampSummary

AWS credentials can be leaked! Here are some ways to stop this or deal with it.

AWS Credentials & types

AWS credentials permit a user to assume an AWS identity. Depending on the type of AWS identity, the identity may also have inherent or assigned permission to access AWS resources and initiate actions with them.

This identity is called a ‘login’, and the identity may be specific to one account or may offer access to several. It is not an account, and by itself has no powers - actions are taken in one or more accounts.

Credentials will include an identifier (username), and a password. Further protections to assuming an identity may include one of several types of Multi-factor Authentication (MFA) tokens or policy limits on the context the identity is valid for (specific account, region, etc). Some types of credentials also include a token which includes hashed details of the username, account, time issued and perhaps other details.

Console vs CLI

The AWS Console is a GUI web interface presenting the state of and controls for an AWS account.

The CLI is the Command Line Interface which is an AWS program which is run in a text terminal which reports about and acts on an AWS account according to program arguments provided when invoked.

Both require an identity and supporting authentication secrets (password, MFA, generated token).

AWS Identities

Account Root user

This identity is created with each new account and has undeniable access to all resources within that account.

The identifier is the email address used to create the account and a password, which may not be set at creation. Optionally, an MFA requirement may be assigned to the identity.

IAM User

This optional identity may be created within an account and has only the permissions granted to it. Optionally, an MFA token may be assigned to the identity.

SSO/IAM Identity Center User

AWS provided a feature named SSO (Single Sign On) and has renamed this to IAM Identity Center, however many documents still refer to SSO, and the CLI command is still named sso.

This feature offers a login, which may then be permitted access to several accounts with varying permissions.

The access may be to the GUI console, or temporary credentials may be given to permit CLI access.

IAM vs SSO

IAM (not SSO) credentials are not time limited, but remain valid until deliberately cancelled. There are situations where IAM users may be useful, but it is generally wise to avoid using them to avoid the possibility of leaking such permanent credentials.

If leaked, they must be actively voided in the AWS Console or via the AWS CLI.

Temporary credentials

SSO credentials are time limited, and must be renewed periodically. When CLI SSO credentials are acquired, a token is included which hashes a timestamp for the time acquired, and the credentials will not be honored after the time the credentials are set to expire. This makes them much safer for use.

Credential leakage, attendent risks

Leaked credentials may be used to carry out the same operations as they are legitimately intended for and often for many other uses as well.

The Internet is surveilled by many actors, and also credentials commited to repositories such as Github and Bitbucket will be noted, harvested, and put into use within minutes. These mis-uses can lead to several negative outcomes:

- Substantial bills for resources.

- Breach of company data.

- Loss of reputation if the breach is publicised.

Defenses

Don’t leak credentials. But how?

AWS has introduced a range of facilities and tools through time to address vulnerabilities of it’s original approaches - IAM users instead of root users, ‘child’ account Roles instead of proliferating IAM users, SSO users with temporary credentials instead of IAM users with permanent credentials, etc.

There are tools to acquire credentials without exposing them and I will not enumerate them here - they change, and reading up-to-date docs is the best way to learn about them.

I will discuss a solution we have developed to invalidate leaked credentials that doesn’t seem to be noted by AWS at the time I’m writing this.

AWS suggestions

AWS has many suggestions for different scenarios. You may start here, but this is certainly not exhaustive: AWS security credentials

Our approaches

Our large clients generally have their own AWS administrators, and they provide their own security approaches, although we may advise them about issues that we encounter. In this section, I’m going to discuss approaches we take in our own company accounts, which support a collection of consultants rather than production systems.

To avoid problems with leaked credentials, we try hard not to use them. In fact, I use them all the time in my administrative work, but I never write them down in a file I might save, so there is no avenue to publish (leak) them.

We avoid using IAM users because those credentials are permanent - we don’t need IAM users generally and thus can’t leak those credentials.

Our account root logins do not have assigned passwords - we always recover the password when we need to operate at that level and we do not save the recovered password - so it is not written anywhere that might be published. We also have a hardware MFA token assigned to each root user and that must be used to recover the password. We only operate as a root user when there is no other option - mostly we only do so to assign that hardware MFA, and we might use it to stop an attack some day.

We use SSO/IAM Identity Center users for our AWS access, and our configuration was set up by AWS Control Tower. Each individual account has it’s own root login, and each could have IAM users, but we gather our accounts into an Organization and access them all through SSO which means the credentials are always temporary, and also subject to some helpful controls.

No invalidation, but credentials may be ignored

SSO credentials, whether for Console access or for CLI use, have temporary lifespans. This lifespan is long enough for serious mischief to occur if leaked to a hostile party, or even a less-competent one.

These SSO credentials do expire, but during their lifespan, they are independent and AWS offers no way to cancel them. However, a conditional clause in a well-targeted policy leads to them being ignored, which may be just as effective.

SCP approach

Control Tower is run from an initial AWS account and designates this account to be the management account. At the same time, an Organization is created, as well as several supporting accounts. Control Tower also creates Permission Sets to apply to accounts in the Organization.

Apart from the management account, all the created accounts and any invited to join the Organization are in the Organization, which provides a mechanism to apply an AWS Service Control Policy (SCP) to any member of the Organization, including the root Organizational Unit (OU). An SCP applied to the root will be enforced on any account or OU in the Organization, and in this way we may apply a blanket policy that applies to all but the management account.

Permission set approach

An SCP has no effect on the management account of an Organization, and so another approach is needed to apply a Policy restriction to that account.

AWS provides several ways to apply a Policy to a Permission Set. The original definition of a Permission Set includes a Policy that determines the permissions it has. As I write this, there are 4 separate ways to apply a Policy to a Permission Set:

- AWS managed policies

- Customer managed policies

- Inline policy

- Permissions boundary

The first two are commonly used to defiine Permissions granted as well as denied. We have experimented with applying a Policy as Inline to limit permissions in the event of a breach. It is necessary to apply this Policy to any Permission Sets used that might provide access using the leaked credentials.

A Policy may have a Conditional stanza attached, such that the Action of the Policy only takes effect if a condition is met, or only takes effect if the condition is not met.

Timestamp

The temporary credentials issued by SSO include a token, and this token carries a timestamp of when it was granted. We can use a Condition to only apply the Policy if the timestamp shows the credentials were granted before a specified time.

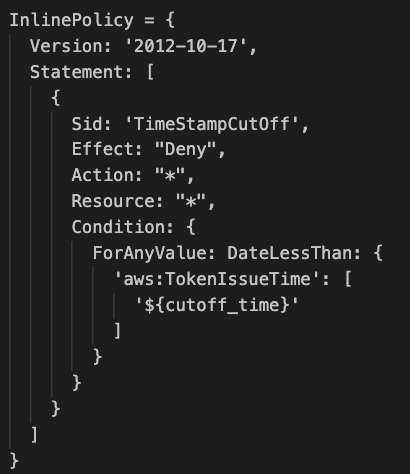

This is an example of a Policy which includes a Condition dependent on the timestamp of the credentials of the user:

InlinePolicy = {

Version: '2012-10-17',

Statement: [

{

Sid: 'TimeStampCutOff',

Effect: "Deny",

Action: "*",

Resource: "*",

Condition: {

ForAnyValue: DateLessThan: {

'aws:TokenIssueTime': [

'${cutoff_time}'

]

}

}

}

]

}

UserId

The token also carries the User ID the permissions were granted to, and a Condition may specify that the permissions of the Policy are granted to, or witheld from, that user.

This may be important in a larger Organization to avoid disrupting activity for others, but it requires identifying the particular user whose credentials have been leaked. As I mentioned above, the majority of our larger clients have their own AWS Administrative and Security teams, and they will implement their approach to this problem.

Our approach

We avoid using credentials outside those granted via the IAM Identify Center, we avoid using permissions that grant access to IAM Identity Center, and we avoid ever writing the credentials we are granted to any file - a file might be transmitted - including tranmission to source control. By these restrictions, we greatly reduce any opportunity to provide credentials to a hostile actors.

Within our own Consultancy, some of our accounts provide Company services, and others provide testbeds for our consultants to use, and there may be activity at any hour, and there often is. We take advantage of a number of AWS supplied alarms and alerts to issues that arise, and have also written some of our own.

As a consequence, an alert might happen at any hour and the person that sees it first may have no knowledge of actions other Consultants may have taken. For this reason, we have implemented a tool that sets timestamp-conditional Policies that ignore any SSO credentials that were issued before the time the tool was invoked. With this, any employee can stop access that results from leaked SSO credentials at any time.

The best security interceptions are the ones you never need to invoke, but if this problem occurs, we know it may be easily stopped.

Recovery from this is simple - by refreshing the AWS login page, we invalidate the cached credentials held by the page and when we then log into our account again it is with new tokens that have timestamps later than specified in the Condition of the limiting Policies that were applied, and we may continue investigating our accounts. But any leaked credentials will not have an updated timestamp and will remain blocked.

DoS risks

Future timestamp attack

This approach to managing leaked credentials relies on a timestamp listed in a Conditional in Policies which deny access to services. If other security protections fail and a hostile actor gains access to our IAM Identify Center console, they could apply a policy with a timestamp in the future, and this would block any SSO credentials we might be issued by AWS. This provides an avenue for a Denial of Service (DoS) attack.

We would mitigate this by signing in to the account as the root user - a login that can’t be denied, and correcting the Permission Sets.

Convenience attack and Robot attack!

There has been discussion of varying front-ends for our Credential Suppression tool - for example posting an update to a repository or posting a message to Slack to shut down access. We do not implement this, and I argue strenuously against it. We avoid the possibility of misuse of our Credential Suppression tool by implementing proper security on our AWS accounts. Adding another layer and API means we must also be experts on that layer, as well as possibly that layer’s interactions with AWS. I prefer to have the simplest understanding of what may occur during what is already an anomalous, and hopefully, rare event.

As well, introducing a front-end layer means there will be an API to access our tool. In that case, an attacker might write a robot that repeatedly invokes the tool before we can refresh our credentials again! Better to keep it simple.

If you need help with your cloud security posture or set up, don’t be shy and get in touch.