The Value of Faster

Tags: bdd devopsThere is a common ‘wisdom’ these days that software development should move faster. From agile to continuous delivery and DevOps, everything is about the need for speed.

But many people struggle to understand the benefits of ‘faster’.

At a gut level people believe that the faster they go the more they are able to do. But is more necessarily better?

Any system is constrained in its throughput by the throughput of its weakest subsystem.

If the purpose of business is to deliver value to customers, and the purpose of development is to modify or create software, then the ability of a business to deliver value via software is determined by the throughput of its software development process. To increase throughput you need to increase capacity of the system or the rate at which it flows.

Is your business constrained in its ability to deliver value via software?

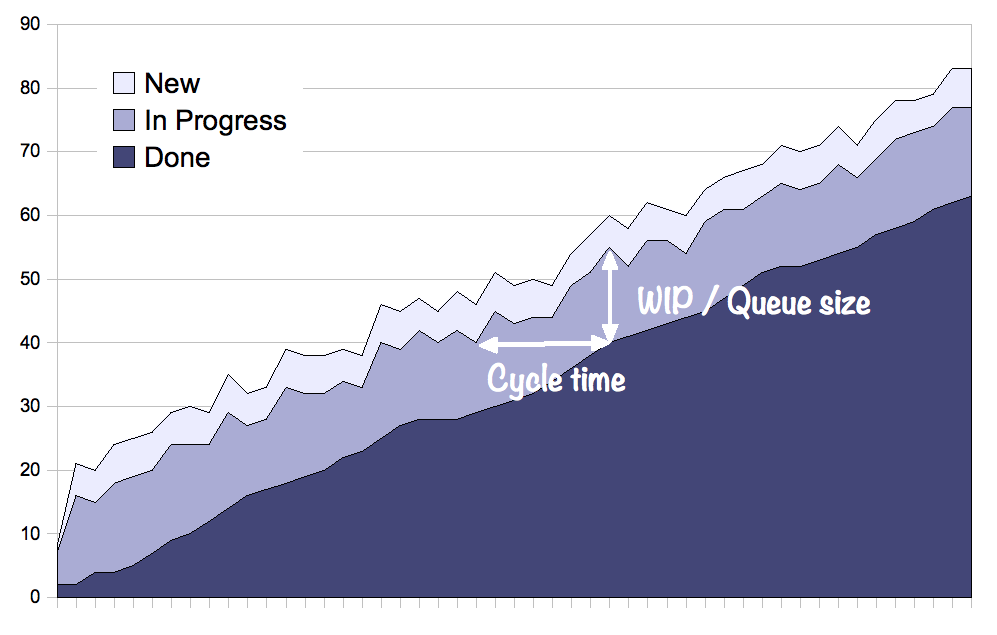

A simple rule of thumb is to look at the change in the demand queue in front of your software development lifecycle. Is it static, or is the queue size increasing? Do you have to purge items from your queue? Is the dwell time in the queue increasing?

If the answer to any of these questions is “yes” then your software development lifecycle represents a bottleneck in the delivery of value to your customers. I’ve never met an organisation yet, where the users and customers struggled to think of new ideas for IT to implement.

Again, most people understand this on a ‘gut’ level, but changing throughput in software development is hard. Adding capacity is costly and delivers diminishing returns.

Increasing the rate of flow is difficult and the overhead inherent in the software development process means that the cost of delivering small changes is astronomically high. Testing, release and deployment all add a cost to a single change that makes it prohibitively expensive, so changes are lumped together into large, long duration projects.

And organisations must decide where to commit scarce resources. Do you commit them to ‘improvement projects’ (which tackle issues like throughput) or to ‘new initiatives’ which deliver some new feature or system for the organisation?

There is a well established machine in most organisations for evaluating the financial benefit of a particular investment. It focuses on measuring the quantitative value delivered by a project in terms like ROI, NPV or IRR. In essence, when choosing which project to do, the organisation will choose the project which returns the most value for an organisation.

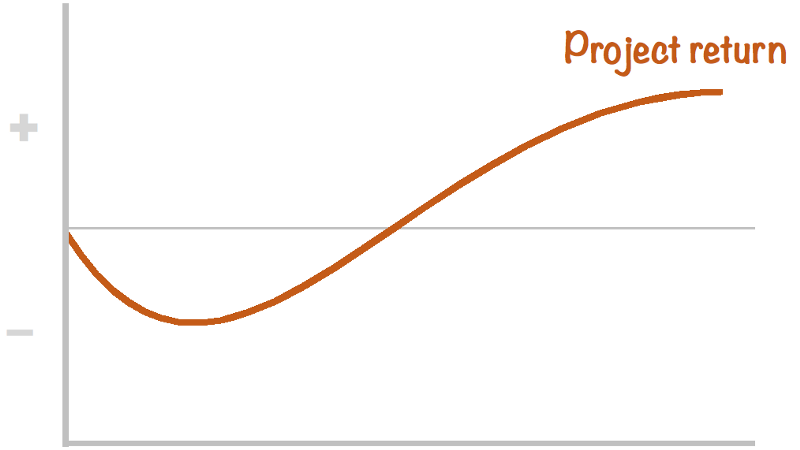

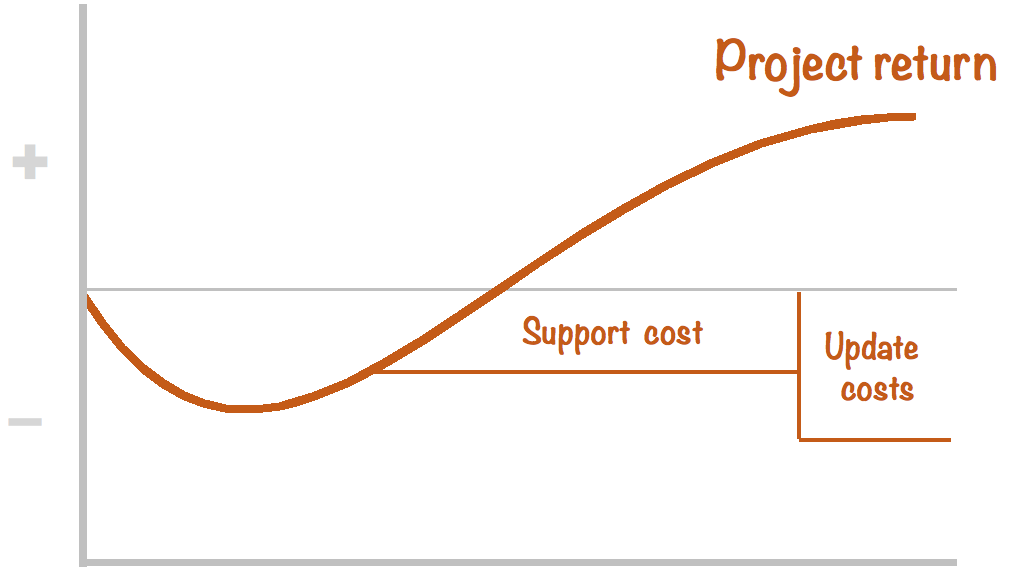

Visually, return on investment can be represented by the following graph:

The initial investment is a cost, which accumulates over time until the project is implemented and starts to deliver benefits. Then it earns out it’s initial investment and (hopefully) returns value to the organisation over time.

The bigger the area under the right hand end of the curve — the higher the value. But it is important to remember that almost all investments have ongoing costs. In the case of software, this is typically ongoing support costs like infrastructure, licensing, updates and service desk support.

Factoring these in erodes the return from later stages of the project. Often ROI models neglect to project far enough out to include the replacement or update costs for a particular initiative. For software these costs typically arise in as little as 2–3 years and can have a significant impact on a project’s commercial viability.

So what is the financial benefit of ‘going faster’?

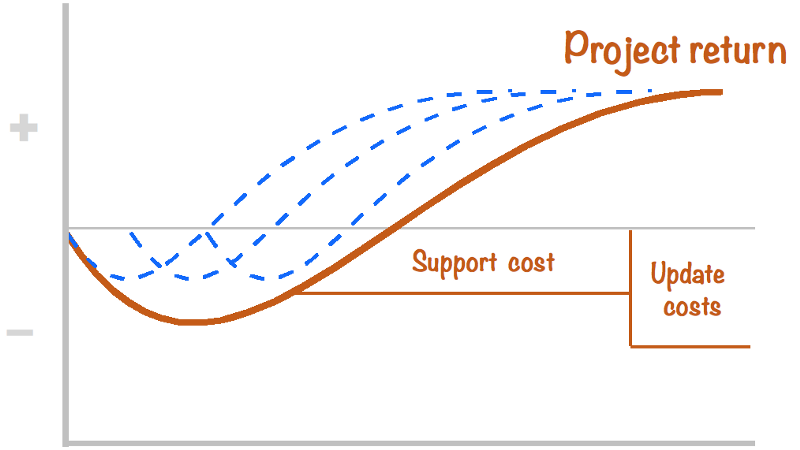

What if you could chunk large projects up into smaller changes that could be delivered quickly?

Using our established model, it is easy to visualise the financial benefit of delivering faster.

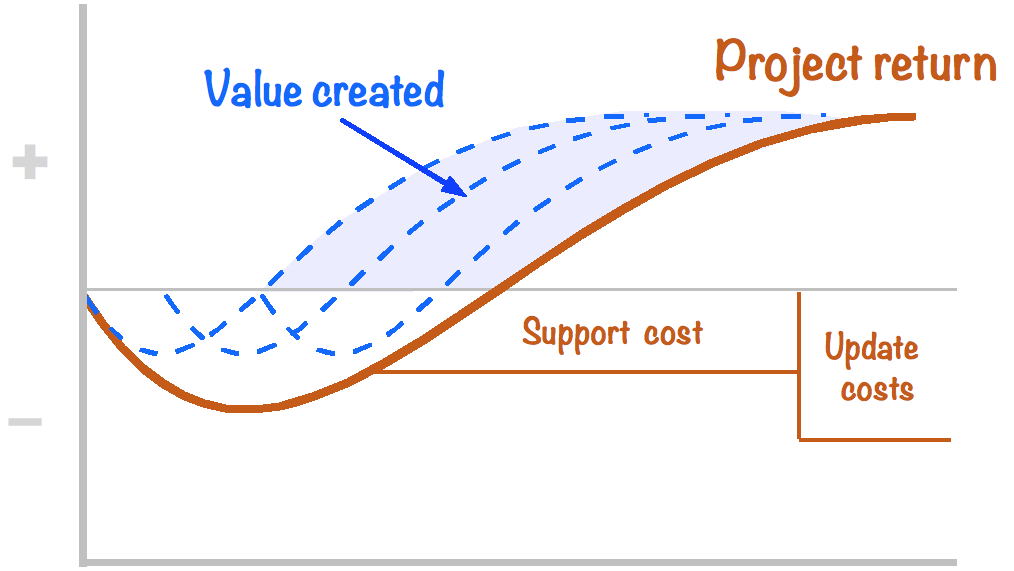

If, instead of delivering large monolithic projects, you were able to deliver smaller chunks much faster, the value can be realised much more quickly. The value of smaller chunks is represented by by the area between the upper curves and the lower, monolithic, project.

Or to flip it on its head, this is the ‘cost of delay’ — the cost of doing large projects.

The cost-of-delay is a well established financial model for investment. To measure the cost-of-delay for a particular investment, you only need model the curve above for your particular product and then calculate the change in cost induced by a one month delay. When used in a sensitivity analysis against other variables such as a change in sales volume or a change in project expenses it readily becomes apparent that the cost-of-delay is (often) the most significant factor in a product’s return of value.

For example studies have shown that the cost of delay is a significant factor in airline scheduling (see Kara, Ferguson, Hoffman and Sherry 2010). It showed that even during periods of increased fuel prices and stricter scheduling, airlines chose to reduce the size of aircraft rather than reduce schedule and increase aircraft size. From the airport’s point of view it is economical to have fewer, larger aircraft delivering more passengers per movement; but for airlines the economics are different and the major factor is not the handling cost an airport, but the cost-of-delay.

The ‘simplistic’ economics of airports are not so simple once you consider the right metrics.

And so it is with software development.

Big projects still get the limelight and are feted but only because we are using the wrong measures. Instead of building elaborate business cases around large projects, we could simply deliver a continuous stream of smaller changes and unlock millions of dollars of value in organisations.

In Australia, like most countries, we’ve had some spectacular big IT project failures : the Queensland Payroll project; the Customs Service Integrated Cargo System and the Victorian HealthSmart project and the IAM project at WA’s Fiona Stanley Hospital. Every organisation has its own trail of woe but spectacular failures often mask more mundane problems — 80–90% of all IT projects fail to deliver the value they promise [Victorian Ombudsman, 2011].

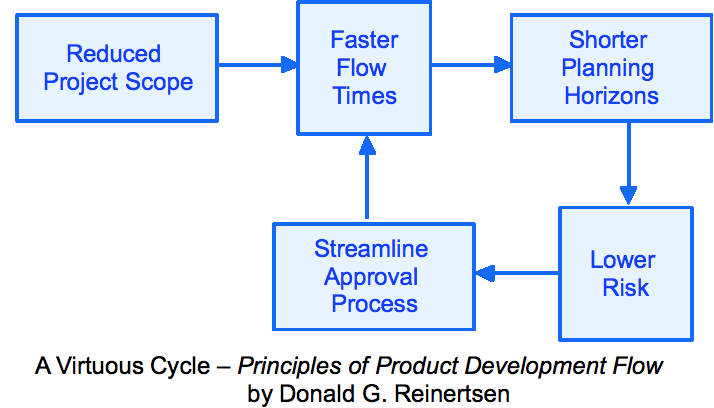

By reducing the size of projects we reduce the risks of failure. By delivering value earlier and in smaller chunks we limit the risk of a larger systematic failure. And there is another benefit in smaller cycles — a faster learning cycle. By delivering smaller chunks we allow ourselves a shorter planning cycle which can react to market or consumer changes more quickly.

So smaller is faster.

Why then do large projects predominate in many organisations? Organisations typically reward star performers and big projects offer many opportunities to be a star. The sponsor, the project manager and the leads can all benefit from the ‘halo effect’ of heroically delivering a difficult project against the odds. But there is much less kudos in quietly and efficiently delivering the same value in a hundred smaller slices.

By standardising (or automating) the repetitive tasks in the software development lifecycle you not only deliver faster but make it more predictable. In statistical terms, you decrease the ‘common cause’ variation in your system which allows you to devote your effort to the ‘special cause’ variation of the complex world of software development. Smaller, repeatable chunks are the path to unlocking value from software.

So where do you start?

Counter-intuitively, one of the first things to do is to reduce your batch size.

This is known as ‘lowering the water level to see the rocks’. By reducing your batch size you can expose the bottlenecks and constraints inherent in your system. If you reduce your batch size to a week’s worth of work, but your change & release procedure takes two weeks to complete, the constraints of your system become apparent.

By lowering the batch size you can expose and tackle the barriers that are limiting your throughput.

And that’s where the work starts.